Breaking Down Traditional Boundaries in Learning Models

For decades, our understanding of how brains learn has been dominated by dual-system theories. These theories suggest that we need separate, complementary learning systems to handle different types of knowledge — one for individual episodes (specific memories) and another for generalizable rules. Similarly, scientists believed there was an inherent trade-off between learning new information and remembering what we already know.

Recent research by Hewson, Sloman, and Dubova challenges these long-held assumptions, revealing that these apparent trade-offs may not be fundamental to learning itself but rather emerge from capacity limitations in the systems being studied.

The Breakthrough: One System Can Handle It All

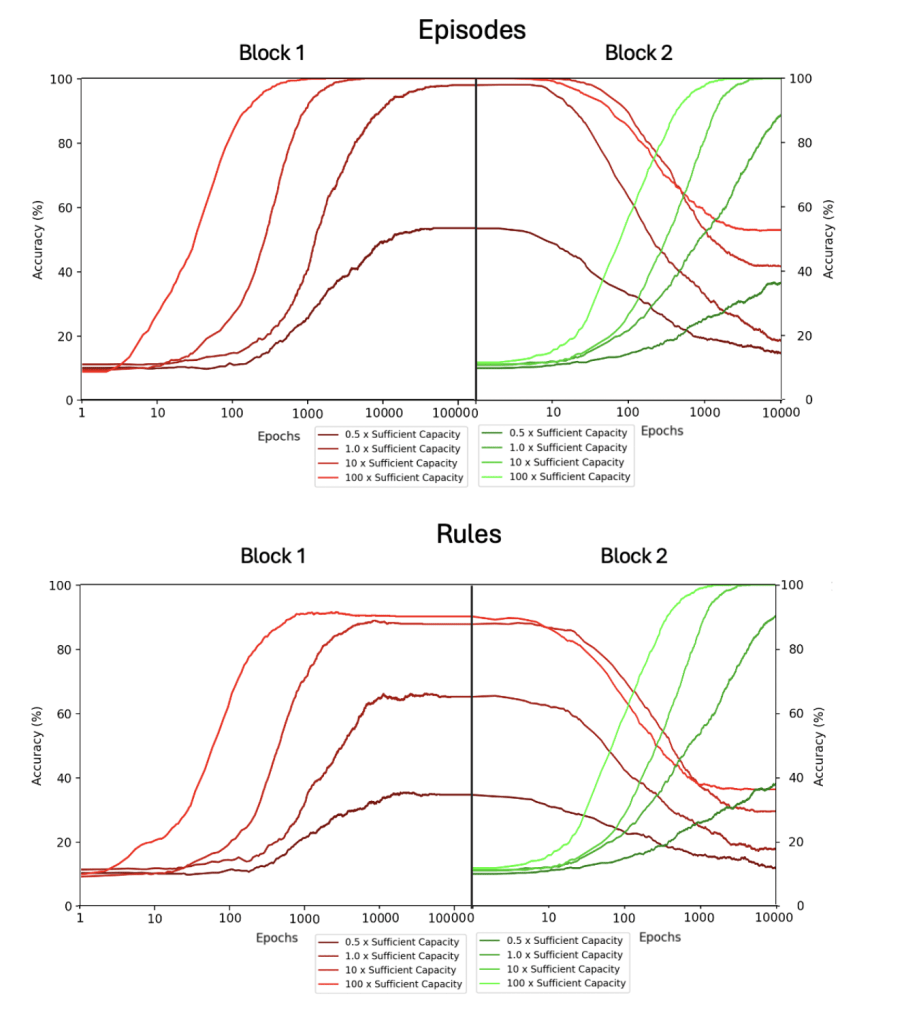

The researchers demonstrate that a single computational learning system with “excess capacity” — meaning it has more representational resources than strictly needed — can simultaneously learn and remember both specific episodes and generalizable rules. This directly challenges the need for separate learning systems that has been a cornerstone of cognitive science for decades.

Their experiments showed that models with excess capacity consistently outperformed constrained models in:

- Learning specific episodes

- Extracting general rules

- Remembering previously learned information while acquiring new knowledge

In essence, when a learning system has abundant capacity, the traditional trade-offs between memorization and generalization, and between learning and remembering, begin to disappear.

Why This Matters: A Complex Systems Perspective

This research aligns beautifully with emerging complex systems theory, which shifts scientific focus away from reductionism toward understanding how complex wholes exhibit properties beyond the sum of their parts.

The traditional approach in neuroscience has been reductionist — breaking down the brain into specialized modules and studying them in isolation. This paper suggests an alternative view: that the brain might be better understood as a unified learning system with distributed excess capacity, rather than as a collection of specialized modules with distinct functions.

Broader Implications

This perspective has profound implications for how we understand learning, memory, and cognition. Rather than focusing on identifying distinct neural systems for different aspects of learning, we might better understand the brain as a single integrated system whose apparent specializations emerge naturally from its distributed learning processes.

At Cyberkind, we believe this shift in perspective is necessary for scientifically appreciating the unique, delicate value of flourishing communities and relationships. Just as the learning system described in this paper achieves its remarkable capabilities through excess distributed capacity rather than through distinct specialized modules, human communities may derive their unique value and capabilities from the richness of their distributed relationships rather than from the mere aggregation of individual contributions.

In both learning systems and human communities, the whole truly becomes greater than the sum of its parts when there is sufficient richness, redundancy, and interconnection.

See the paper at: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.05884

Leave a comment